« 5.0 The Age of Reptiles |Contents | 5.2 Flying Dragons »

5.1 The Age of Lowland Life¶

We know that for hundreds of thousands of years the wetness and warmth, the shallow lagoon conditions that made possible the vast accumulations of vegetable matter which, compressed and mummified, are now coal[1], prevailed over most of the world. There were some cold intervals, it is true; but they did not last long enough to destroy the growths. Then that long ago age of luxuriant low-grade vegetation drew to its end, and for a time life on the earth seems to have undergone a period of world-wide bleakness.

We cannot discuss fully here the changes that have gone on and are going on in the climate of the earth. A great variety of causes, astronomical movements, changes in the sun and changes upon and within the earth, combine to produce a ceaseless fluctuation of the conditions under which life exists. As these conditions change, life, too, must change or perish.

When the story resumes again after this arrest at the end of the Paleozoic period we find life entering upon a fresh phase of richness and expansion. Vegetation has made great advances in the art of living out of water. While the Paleozoic plants of the coal measures probably grew with swamp water flowing over their roots, the Mesozoic flora from its very outset included palm-like cycads and low-grown conifers that were distinctly land plants growing on soil above the water level.

The lower levels of the Mesozoic land were no doubt covered by great fern brakes and shrubby bush and a kind of jungle growth of trees. But there existed as yet no grass, no small flowering plants, no turf nor greensward. Probably the Mesozoic was not an age of very brightly coloured vegetation. It must have had a flora green in the wet season and brown and. purple in the dry. There were no gay flowers, no bright autumn tints before the fall of the leaf, because there was as yet no fall of the leaf. And beyond the lower levels the world was still barren, still unclothed, still exposed without any mitigation to the wear and tear of the wind and rain.

When one speaks of conifers in the Mesozoic the reader must not think of the pines and firs that clothe the high mountain slopes of our time. He must think of low-growing evergreens. The mountains were still as bare and lifeless as ever. The only colour effects among the mountains were the colour effects of naked rock, such colours as make the landscape of Colorado so marvelous today.

Amidst this spreading vegetation of the lower plains the reptiles were increasing mightily in multitude and variety. They were now in many cases absolutely land animals. There are numerous anatomical points of distinction between a reptile and an amphibian; they held good between such reptiles and amphibians as prevailed in the carboniferous time of the Upper Paleozoic; but the fundamental difference between reptiles and amphibia which matters in this history is that the amphibian must go back to the water to lay its eggs, and that in the early stages of its life it must live in and under water. The reptile, on the other hand, has cut out all the tadpole stages from its life cycle, or, to be more exact, its tadpole stages are got through before the young leave the egg case. The reptile has come out of the water altogether. Some had gone back to it again, just as the hippopotamus and the otter among mammals have gone back, but that is a further extension of the story to which we cannot give much attention in this Outline.

In the Paleozoic period, as we have said, life had not spread beyond the swampy river valleys and the borders of sea lagoons and the like; but in the Mesozoic, life was growing ever more accustomed to the thinner medium of the air, was sweeping boldly up over the plains and towards the hill-sides. It is well for the student of human history and the human future to note that. If a disembodied intelligence with no knowledge of the future had come to earth and studied life during the early Paleozoic age, he might very reasonably have concluded that life was absolutely confined to the water, and that it could never spread over the land. It found a way. In the Later Paleozoic Period that visitant might have been equally sure that life could not go beyond the edge of a swamp. The Mesozoic Period would still have found him setting bounds to life far more limited than the bounds that are set today. And so today, though we mark how life and, man are still limited to five miles of air and a depth of perhaps a mile or so of sea, we must not conclude from that present limitation that life, through man, may not presently spread out and up and down to a range of living as yet inconceivable.

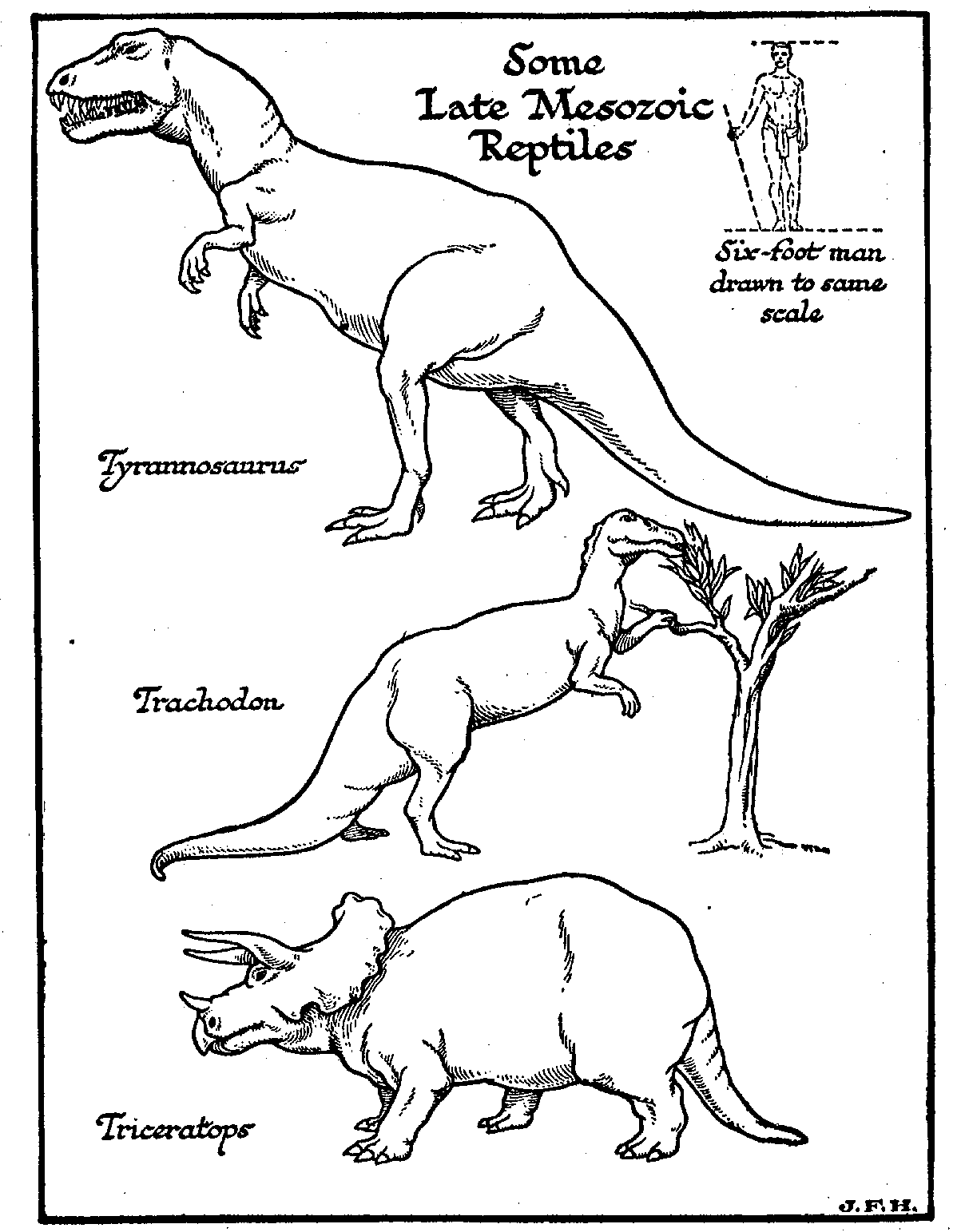

The earliest known reptiles were beasts with great bellies and not very powerful legs, very like their kindred amphibia, wallowing as the crocodile wallows to this day; but, in the Mesozoic they soon began to stand up and go stoutly on all fours, and several great sections of them began to balance themselves on tail and hind-legs, rather as the kangaroos do now, in order to release the fore limbs for grasping food. The bones of one notable division of reptiles which retained a quadrupedal habit, a division of which many remains have been found in South African and Russian Early Mesozoic deposits, display a number of characters which approach those of the mammalian skeleton, and because of this resemblance to the mammals (beasts) this division is called the Theriomorpha (beastlike). Another division was the crocodile branch, and, another developed towards the tortoises and turtles. The Plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs were two groups which have left no living representatives; they were huge reptiles returning to a whale-like life in the sea. Pliosaurus, one of the largest plesiosaurs, measured thirty feet from snout to tail tip – of which half was neck. The Mosasaurs were a third group of great porpoise-like marine lizards. But the largest and most diversified group of these Mesozoic reptiles was the group we have spoken of as kangaroo-like, the Dinosaurs, many of which attained, enormous proportions. In bigness these greater Dinosaurs have never been exceeded, although the sea can still show in the whales creatures as great. Some of these, and the largest among them, were herbivorous animals; they browsed on the rushy vegetation and among the ferns and bushes, or they stood up and grasped trees with their fore-legs while they devoured the foliage. Among the browsers, for example, were the Diplodocus carnegii, which measured eighty- four feet in length, and the Atlantosaurus. The Gigantosaurus, disinterred by a German expedition in 1912 from rocks in East Africa, was still more colossal. It measured well over a hundred feet! These greater monsters had legs, and they are usually figured as standing up on them; but it is very doubtful if they could, have supported their weight in this way, out of water. Buoyed up by water or mud, they may have got along. Another noteworthy type we have figured is the Triceratops. There were also a number of great flesh-eaters who preyed upon these herbivores. Of these, Tyrannosaurus seems almost the last word in “frightfulness” among living things. Some species of this genus measured forty feet from snout to tail. Apparently it carried this vast body kangaroo, fashion on its tail and hind legs. Probably it reared itself up. Some authorities even suppose that it leapt through the air. If so, it possessed muscles of a quite miraculous quality. A leaping elephant would be a far less astounding idea. Much more probably it waded half submerged in pursuit of the herbivorous river saurians.

Footnotes

| [1] | Dr. Marie Stopes, Monograph on the Constitution of Coal. |

« 5.0 The Age of Reptiles |Contents | 5.2 Flying Dragons »

comments powered by Disqus