« 25.3 The Gospel of Gautama Buddha |Contents | 25.5 Two Great Chinese Teachers »

25.4 Buddhism and Asoka[1]¶

From the very first this new teaching was misconceived. One corruption was perhaps inherent in its teaching. Because the world of men had as yet no sense of the continuous progressive effort of life, it was very easy to slip from the idea of renouncing self to the idea of renouncing active life. As Gautama’s own experiences had shown, it is easier to flee from this world than from self. His early disciples were strenuous thinkers and teachers, but the lapse into mere monastic seclusion was a very easy one, particularly easy in the climate of India, where an extreme simplicity of living is convenient and attractive, and exertion more laborious than anywhere else in the world.

And it was early the fate of Gautama, as it has been the fate of most religious founders since his days, to be made into a wonder by his less intelligent disciples in their efforts to impress the outer world. We have already noted how one devout follower could not but believe that the moment of the master’s mental irradiation must necessarily have been marked by an epileptic fit of the elements. This is one small sample of the vast accumulation of vulgar marvels that presently sprang up about the memory of Gautama.

There can be no doubt that for the great multitude of human beings then as now the mere idea of an emancipation from self is a very difficult one to grasp. It is probable that even among the teachers Buddha was sending out from Benares there were many who did not grasp it and still less were able to convey it to their hearers. Their teaching quite naturally took on the aspect of salvation not from oneself–that idea was beyond them–but from misfortunes and sufferings here and hereafter. In the existing superstitions of the people, and especially in the idea of the transmigration of the soul after death, though this idea was contrary to the Master’s own teaching, they found stuff of fear they could work upon. They urged virtue upon the people lest they should live again in degraded or miserable forms, or fall into some one of the innumerable hells of torment with which the Brahminical teachers had already familiarized their minds. They represented Buddha as the saviour from almost unlimited torment.

There seems to be no limit to the lies that honest but stupid disciples will tell for the glory of their master and for what they regard as the success of their propaganda. Men who would scorn to tell a lie in everyday life will become unscrupulous cheats and liars when they have given themselves up to propagandist work; it is one of the perplexing absurdities of our human nature. Such honest souls, for most of them were indubitably honest, were presently telling their hearers of the miracles that attended the Buddha’s birth–they no longer called him Gautama, because that was too familiar a name–of his youthful feats of strength, of the marvels of his everyday life, winding up with a sort of illumination of his body at the moment of death. Of course it was impossible to believe that Buddha was the son of a mortal father. He was miraculously conceived through his mother dreaming of a beautiful white elephant! Previously he had himself been a, marvellous elephant with six tusks; he had generously given them all to a needy hunter–and even helped him to saw them off. And so on.

Moreover, a theology grew up about Buddha. He was discovered to be a god. He was one of a series of divine beings, the Buddhas. There was an undying «Spirit of all the Buddhas»; there was a great series of Buddhas past and Buddhas (or Bodhisattvas) yet to come. But we cannot go further into these complications of Asiatic theology. «Under the overpowering influence of these sickly imaginations the moral teachings of Gautama have been almost hid from view.

The theories grew and flourished; each new step, each new hypothesis, demanded another; until the whole sky was filled with forgeries of the brain, and the nobler and simpler lessons of the founder of the religion were smothered beneath the glittering mass of metaphysical subtleties».[2]

In the third century B.C. Buddhism was gaining wealth and power, and the little groups of simple huts in which the teachers of the Order gathered in the rainy season were giving place to substantial monastic buildings. To this period belong the beginnings of Buddhistic art. Now if we remember how recent was the adventure of Alexander, that all the Punjab was still under Seleucid rule, that all India abounded with Greek adventurers, and that there was still quite open communication by sea and land with Alexandria, it is no great wonder to find that this early Buddhist art was strongly Greek in character, and that the new Alexandrian cult of Serapis and Isis was extraordinarily influential in its development.

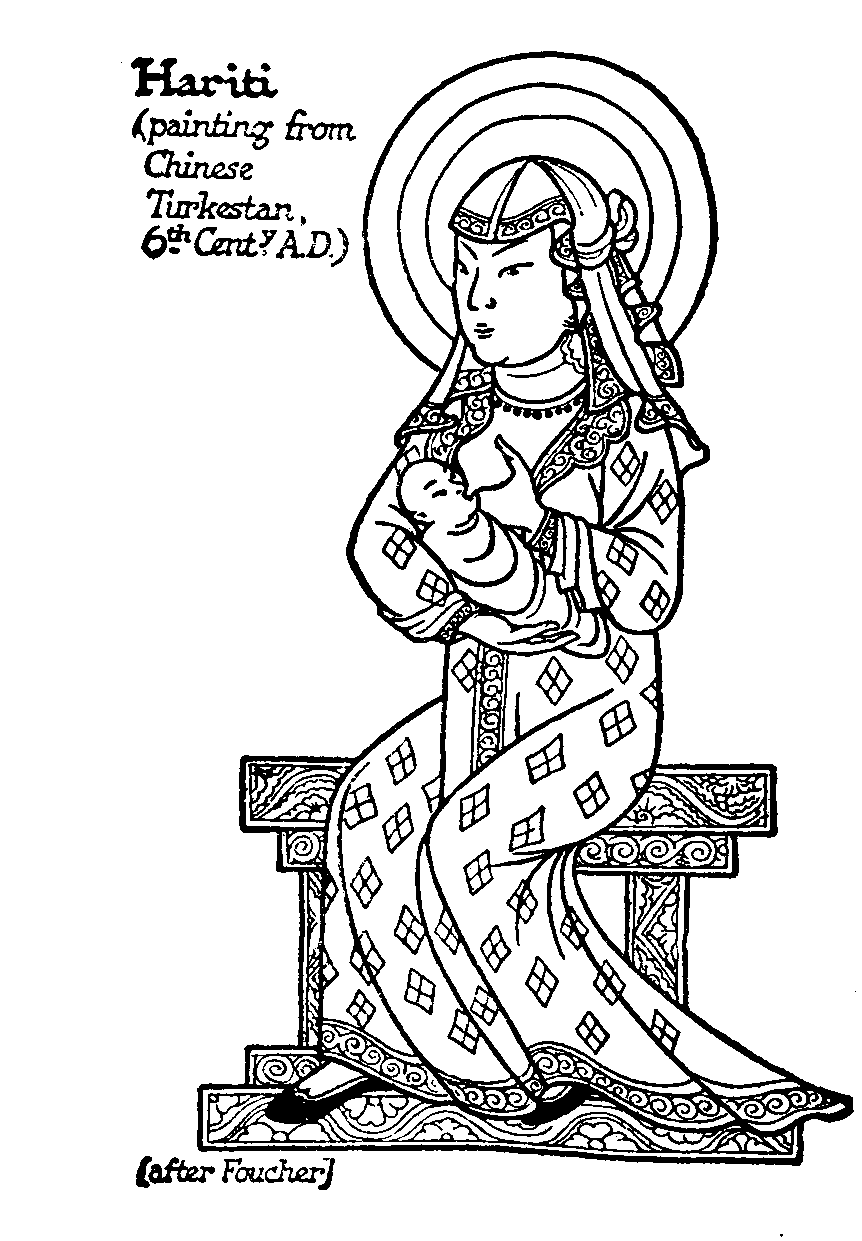

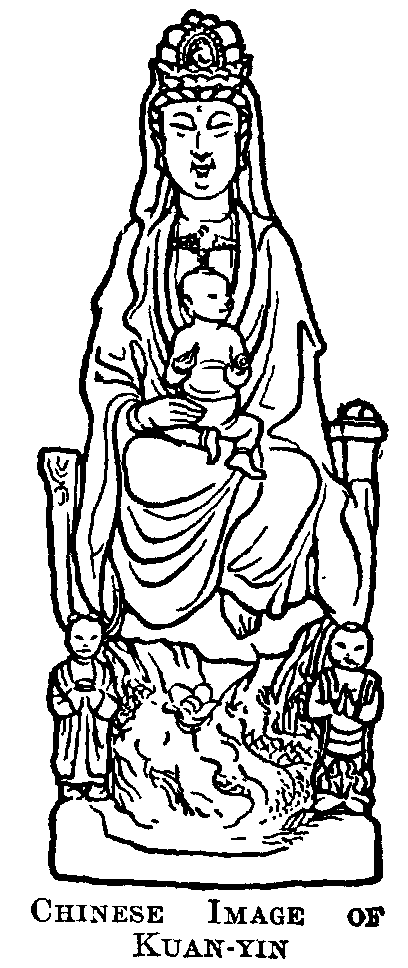

The kingdom of Gandhara on the north-west frontier near Peshawar, which flourished in the third century B.C. was a typical meeting-place of the Hellenic and Indian worlds. Here are to be found the earliest Buddhist sculptures, and interwoven with them are figures which are recognizably the figures of Serapis and Isis and Horus already worked into the legendary net that gathered about Buddha. No doubt the Greek artists who came to Gandhara were loath to relinquish a familiar theme. But Isis, we are told, is no longer Isis but Hariti, a pestilence goddess whom Buddha converted and made benevolent. Foucher traces Isis from this centre into China, but here other influences were also at work, and the story becomes too complex for us to disentangle in this Outline.[3] China had a Taoist deity, the Holy Mother, the Queen of Heaven, who took on the name, (originally a male name) of Kuan-yin and who came to resemble the Isis figure very closely. The Isis figures, we feel, must have influenced the treatment of Kuan-yin. Like Isis she was also Queen of the Seas, Stella Maris. In Japan she was called Kwannon. There seems to have been a constant exchange of the outer forms of religion between east and west. We read in Hue’s Travels how perplexing he and his fellow missionary found this possession of a common tradition of worship. «The cross», he says, «the mitre, the dalmatica, the cope which the Grand Lamas wear on their journeys, or when they are performing some ceremony out of the temple; the service with double choirs, the psalmody, the exorcisms, the censer, suspended from five chains, which you can open or close at pleasure; the benedictions given by the Lamas by extending the right hand over the heads of the faithful; the chaplet, ecclesiastical celibacy spiritual retirement, the worship of the saints, the fasts, the processions, the litanies, the holy water, all these are analogies between the Buddhists and ourselves». [4]

The cult and doctrine of Gautama, gathering corruptions and variations from Brahminism and Hellenism alike, was spread throughout India by an increasing multitude of teachers in the fourth and third centuries B.C. For some generations at least it retained much of the moral beauty and something of the simplicity of the opening phase. Many people who have no intellectual grasp upon the meaning of self-abnegation and disinterestedness have nevertheless the ability to appreciate a splendour in the reality of these qualities. Early Buddhism was certainly producing noble lives, and it is not only through reason that the latent response to nobility is aroused in our minds. It spread rather in spite of than because of the concessions that it made to vulgar imaginations. It spread because many of the early Buddhists were sweet and gentle, helpful and noble and admirable people, who compelled belief in their sustaining faith.

Quite early in its career Buddhism came into conflict with the growing pretensions of the Brahmins. As we have already noted, this priestly caste was still only struggling to dominate Indian life in the days of Gautama. They had already great advantages. They had the monopoly, of tradition and religious sacrifices. But their power was being challenged by the development of kingship, for the men who became clan leaders and kings were usually not of the Brahminical caste.

Kingship received an impetus from the Persian and Greek invasions of the Punjab. We have already noted the name of King Porus whom, in spite of his elephants, Alexander defeated and turned into a satrap. There came also to the Greek camp upon the Indus a certain adventurer named Chandragupta Maurya, whom the Greeks called Sandracottus, with a scheme for conquering the Ganges country.

The scheme was not welcome to the Macedonians, who were in revolt against marching any further into India, and he had to fly the camp. He wandered among the tribes upon the north-west frontier, secured their support, and after Alexander had departed, overran the Punjab, ousting the Macedonian representatives. He then conquered the Ganges country (321 B.C.), waged a successful war (303 B.C.) against Seleucus (Seleucus I) when the latter attempted to recover the Punjab, and consolidated a great empire reaching across all the plain of northern India from the western to the eastern sea. And this King Chandragupta came into much the same conflict with the growing power of the Brahmins, into the conflict between crown and priesthood, that we have already noted as happening in Babylonia and Egypt and China. He saw in the spreading doctrine of Buddhism an ally against the growth of priestcraft and caste. He supported and endowed the Buddhistic Order, and encouraged its teachings.

He was succeeded by his son, who conquered Madras and was in turn succeeded by Asoka (264 to 227 B.C.), one of the great monarchs of history, whose dominions extended from Afghanistan to Madras. He is the only military monarch on record who abandoned warfare after victory. He had invaded Kalinga (255 B.C.), a country along the east coast of Madras, perhaps with some intention of completing the conquest of the tip of the Indian peninsula. The expedition was successful, but he was disgusted by what be saw of the cruelties and horrors of war. He declared, in certain inscriptions that still exist, that he would no longer seek conquest by war, but by religion, and the rest of his life was devoted to the spreading of Buddhism throughout the world.

He seems to have ruled his vast empire in peace and with great ability. He was no more religious fanatic. But in the year of his one and only war he joined the Buddhist community as a layman, and some years later he became a full member of the Order, and devoted himself to the attainment of Nirvana by the Eightfold Path.

How entirely compatible that way of living then was with the most useful and beneficent activities his life shows. Right Aspiration, Right Effort, and Right Livelihood distinguished his career. He organized a great digging of wells in India, and the planting of trees for shade. He appointed officers for the supervision of charitable works. He founded hospitals and public gardens. He had gardens made for the growing of medicinal herbs. Had he had an Aristotle to inspire him, he would no doubt have endowed scientific research upon a great scale. He created a ministry for the care of the aborigines and subject races. He made provision for the education of women. He made, he was the first monarch to make, an attempt to educate his people into a common view of the ends and way of life. He made vast benefactions to the Buddhist teaching orders, and tried to stimulate them to a better study of their own literature. All over the land beset up long inscriptions rehearsing the teaching of Gautama, and it is the simple and human teaching and not the preposterous accretions. Thirty-five of his inscriptions survive to this day. Moreover, he sent missionaries to spread the noble and reasonable teaching of his master throughout the world, to Kashmir, to Ceylon, to the Seleucids, and the Ptolemies. It was one of these missions which carried that cutting of the Bo Tree, of which we have already told, to Ceylon.

For eight and twenty years Asoka worked sanely for the real needs of men. Amidst the tens of thousands of names of monarchs that crowd the columns of history, their majesties and graciousnesses and serenities and royal highnesses and the like, the name of Asoka shines, and shines, almost alone, a star. From the Volga to Japan his name is still honoured. China, Tibet, and even India, though it has left his doctrine, preserve the tradition of his greatness. More living men cherish his memory today than have ever heard the names of Constantine or Charlemagne.

| [1] | Pronounced “Ashoka” |

| [2] | Rhys Davids, Buddhism. |

| [3] | See R. F. Johnston, Buddhist China. —L. C. B. |

| [4] | Hue’s Travels in Tartary, Thibet, and China. |

« 25.3 The Gospel of Gautama Buddha |Contents | 25.5 Two Great Chinese Teachers »

comments powered by Disqus