« 23.2 The Murder of King Philip |Contents | 23.4 The Wanderings of Alexander »

23.3 Alexander’s First Conquests¶

These stories have to be told because history cannot be understood without them. Here was the great world of men between India and the Adriatic ready for union, ready as it had never been before for a unifying control. Here was the wide order of the Persian Empire with its roads, its posts, its general peace and prosperity, ripe for the fertilizing influence of the Greek mind. And these stories display the quality of the human beings to whom those great opportunities came. Here was this Philip who was a very great and noble man, and yet he was drunken, he could keep no order in his household. Here was Alexander in many ways gifted above any man of his time, and he was vain, suspicious, and passionate, with a mind set awry by his mother.

We are beginning to understand something of what the world might be, something of what our race might become, were it not for our still raw humanity. It is barely a matter of seventy generations between ourselves and Alexander; and between ourselves and the savage hunters, our ancestors, who charred their food in the embers or ate it raw, intervene some four or five hundred generations. There is not much scope for the modification of a species in four or five hundred generations. Make men and women only sufficiently jealous or fearful or drunken or angry, and the hot red eyes of the cavemen will glare out at us today. We have writing and teaching, science and power; we have tamed the beasts and schooled the lightning; but we are still only shambling towards the light. We have tamed and bred the beasts, but we have still to tame and breed ourselves.

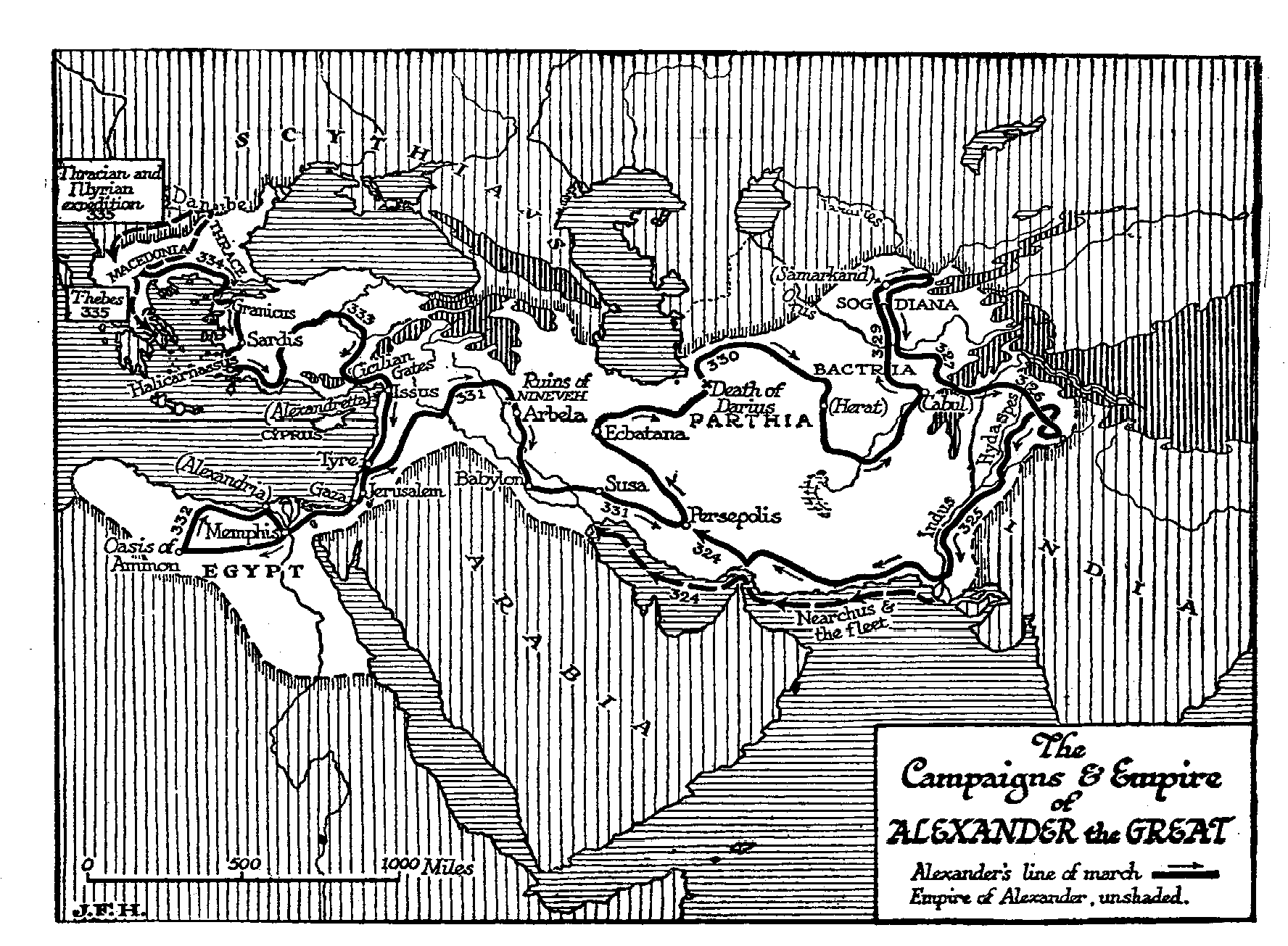

From the very beginning of his reign the deeds of Alexander showed how well he had assimilated his father’s plans, and how great were his own abilities. A map of the known world is needed to show the course of his life. At first, after receiving assurances from Greece that he was to be captain-general of the Grecian forces, he marched through Thrace to the Danube; he crossed the river and burnt a village, the second great monarch to raid the Scythian country beyond the Danube; then recrossed it and marched westward and so came down by Illyria. By that time the city of Thebes was in rebellion, and his next blow was at Greece. Thebes – unsupported of course by Athens – was taken and looted; it was treated with extravagant violence; all its buildings, except the temple and the house of the poet Pindar, were razed, and thirty thousand people sold into slavery. Greece was stunned, and Alexander was free to go on with the Persian campaign.

This destruction of Thebes betrayed a streak of violence in the new master of human destinies. It was too heavy a blow to have dealt. It was a barbaric thing to do. If the spirit of rebellion was killed, so also was the spirit of help. The Greek states remained inert thereafter, neither troublesome nor helpful. They would not support Alexander with their shipping, a thing which was to prove a very grave embarrassment to him.

There is a story told by Plutarch about this Theban massacre, as if it redounded to the credit of Alexander, but indeed it shows only how his saner and his crazy sides were in conflict. It tells of a Macedonian officer and a Theban lady. This officer was among the looters, and he entered this woman’s house, inflicted unspeakable insults and injuries upon her, and at last demanded whether she had gold or silver hidden. She told him all her treasures had been put into the well, conducted him thither, and, as be stooped to peer down, pushed him suddenly in and killed him by throwing great stones upon him. Some allied soldiers came upon this scene and took her forthwith to Alexander for judgment.

She defied him. Already the extravagant impulse that had ordered the massacre was upon the wane, and he not only spared her, but had her family and property and freedom restored to her. This Plutarch makes out to be a generosity, but the issue is more complicated than that. It was Alexander who was outraging and plundering and enslaving all Thebes. That poor crumpled Macedonian brute in the well had been doing only what he had been told he had full liberty to do. Is a commander first to give cruel orders, and then to forgive and reward those who slay his instruments? This gleam of remorse at the instance of one woman who was not perhaps wanting in tragic dignity and beauty, is a poor setoff to the murder of a great city.

Mixed with the craziness of Olympias in Alexander was the sanity of Philip and the teachings of Aristotle. This Theban business certainly troubled the mind of Alexander. Whenever afterwards he encountered Thebans, he tried to show them special favour. Thebes, to his credit, haunted him.

Yet the memory of Thebes did not save three other great cities from similar brain storms; Tyre he destroyed, and Gaza, and a city in India, in the storming of which he was knocked down in fair fight and wounded; and of the latter place not a soul, not a child, was spared. He must have been badly frightened to have taken so evil a revenge.

At the outset of the war the Persians had this supreme advantage, they were practically masters of the sea. The ships of the Athenians and their allies sulked unhelpfully. Alexander, to get at Asia, had to go round by the Hellespont; and if he pushed far into the Persian empire, he ran the risk of being cut off completely from his base. His first task, therefore, was to cripple the enemy at sea, and this he could only do by marching along the coast of Asia Minor and capturing port after port until the Persian sea bases were destroyed. If the Persians had avoided battle and hung upon his lengthening line of communications they could probably have destroyed him, but this they did not do. A Persian army not very much greater than his own gave battle on the banks of the Granicus (334 B.C.) and was destroyed. This left him free to take Sardis, Ephesus, Miletus, and, after a fierce struggle, Halicarnassus. Meanwhile the Persian fleet was on his right flank and between him and Greece, threatening much but accomplishing nothing.

In 333 B.C., pursuing this attack upon the sea bases, he marched along the coast as far as the head of the gulf now called the Gulf of Alexandretta. A huge Persian army, under the great king Darius III, was inland of his line of march, separated from the coast by mountains, and Alexander went right beyond this enemy force before he or the Persians realized their proximity. Scouting was evidently very badly done by Greek and Persian alike. The Persian army was a vast, ill-organized assembly of soldiers, transport, camp followers, and so forth. Darius, for instance, was accompanied by his harem, and there was a great multitude of harem slaves, musicians, dancers, and cooks. Many of the leading officers had brought their families to witness the hunting down of the Macedonian invaders. The troops had been levied from every province in the empire; they had no tradition or principle of combined action. Seized by the idea of cutting off Alexander from Greece, Darius moved this multitude over the mountains to the sea; he had the luck to get through the passes without opposition, and he encamped on the plain of Issus between the mountains and the shore. And there Alexander, who had turned back to fight, struck him. The cavalry charge and the phalanx smashed this great brittle host as a stone smashes a bottle. It was routed. Darius escaped from his war chariot – that out-of-date instrument – and fled on horseback, leaving even his harem in the hands of Alexander.

All the accounts of Alexander after this battle show him at his best. He was restrained and magnanimous. He treated the Persian princesses with the utmost civility. And he kept his head; he held steadfastly to his plan. He let Darius escape, unpursued, into Syria, and he continued his march upon the naval bases of the Persians – that is to say, upon the Phoenician ports of Tyre and Sidon.

Sidon surrendered to him; Tyre resisted.

Here, if anywhere, we have the evidence of great military ability on the part of Alexander. His army was his father’s creation, but Philip had never shone in the siege of cities. When Alexander was a boy of sixteen, he had seen his father repulsed by the fortified city of Byzantium upon the Bosphorus. Now he was face to face with an inviolate city which had stood siege after siege, which had resisted Nebuchadnezzar the Great for fourteen years.

For the standing of sieges Semitic peoples hold the palm. Tyre was then an island half a mile from the shore, and her fleet was unbeaten. On the other hand, Alexander had already learnt much by the siege of the citadel of Halicarnassus; he had gathered to himself a corps of engineers from Cyprus and Phoenicia the Sidonian fleet was with him, and presently the king of Cyprus came over to him with a hundred and twenty ships, which gave him the command of the sea. Moreover, great Carthage, either relying on the strength of the mother city or being disloyal to her, and being furthermore entangled in a war in Sicily, sent no help.

The first measure of Alexander was to build a pier from the mainland to the island, a dam which remains to this day; and on this, as it came close to the walls of Tyre, he set up his towers and battering-rams. Against the walls he also moored ships in which towers and rams were erected. The Tyrians used fire-ships against this flotilla, and made sorties from their two harbours. In a big surprise raid that they made on the Cyprian ships they were caught and badly mauled; many of their ships were rammed, and one big galley of five banks of oars and one of four were captured outright. Finally a breach in the walls was made, and the Macedonians, clambering up the debris from their ships, stormed the city.

The siege had lasted seven months. Gaza held out far two. In each case there was a massacre, the plundering of the city, and the selling of the survivors into slavery. Then towards the end of 332 B.C. Alexander entered Egypt, and the command of the sea was assured. Greece, which all this while had been wavering in its policy, decided now at last that it was an the side of Alexander, and the council of the Greek states at Corinth voted its «captain-general» a golden crown of victory. From this time onward the Greeks were with the Macedonians.

The Egyptians also were with the Macedonians. But they had been for Alexander from the beginning. They had lived under Persian rule for nearly two hundred years, and the coming of Alexander meant for them only a change of masters; on the whole, a change for the better. The country surrendered without a blow. Alexander treated its religious feelings with extreme respect. He unwrapped no mummies as Cambyses had done; he took no liberties with Apis, the sacred bull of Memphis. Here, in great temples and upon a vast scale, Alexander found the evidences of a religiosity, mysterious and irrational, to remind him of the secrets and mysteries that had entertained his mother and impressed his childhood. During his four months in Egypt he flirted with religious emotions.

He was still a very young man, we must remember, divided against himself. The strong sanity he inherited from his father had made him a great soldier; the teaching of Aristotle had given him something of the scientific outlook upon the world. He had destroyed Tyre; in Egypt, at one of the mouths of the Nile, he now founded a new city, Alexandria, to replace that ancient centre of trade. To the north of Tyre, near Issus, he founded a second port, Alexandretta. Both of these cities flourish to this day, and for a time Alexandria was perhaps the greatest city in the world. The sites, therefore, must have been wisely chosen. But also Alexander had the unstable emotional imaginativeness of his mother, and side by side with such creative work he indulged in religious adventures. The gods of Egypt took possession of his mind. He travelled four hundred miles to the remote oasis of the oracle of Ammon. He wanted to settle certain doubts about his true parentage. His Mother had inflamed his mind by hints and vague speeches of some deep mystery about his parentage. Was so ordinary a human being as Philip of Macedon really his father?

For nearly four hundred years Egypt, had been a country politically contemptible, overrun now by Ethiopians, now by Assyrians, now by Babylonians, now by Persians. As the indignities of the present became more and more disagreeable to contemplate, the past and the other world became more splendid to Egyptian eyes. It is from the festering humiliations of peoples that arrogant religious propagandas spring. To the triumphant the downtrodden can say, «It is naught in the sight of the true gods». So the son of Philip of Macedon, the master-general of Greece, was made to feel a small person amidst the gigantic temples. And he had an abnormal share of youth’s normal ambition to impress everybody. How gratifying then for him to discover presently that he was no mere successful mortal, not one of these modern vulgar Greekish folk, but ancient and divine, the son of a god, the Pharaoh god, son of Ammon Ra!

Already in a previous chapter we have given a description of that encounter in the desert temple.

Not altogether was the young man convinced. He had his moments of conviction; he had his saner phases when the thing was almost a jest. In the presence of Macedonians and Greeks he doubted if he was divine. When it thundered loudly, the ribald Aristarchus could ask him: «Won’t you do something of the sort, oh Son of Zeus?» But the crazy notion was, nevertheless, present henceforth in his brain, ready to be inflamed by wine or flattery.

Next spring (331 B.C.) he returned to Tyre, and marched thence round towards Assyria, leaving the Syrian desert on his right. Near the ruins of forgotten Nineveh he found a great Persian army, that had been gathering since the battle of Issus, awaiting him. It was another huge medley of contingents, and it relied for its chief force upon that now antiquated weapon, the war chariot. Of these Darius had a force of two hundred, and each chariot had scythes attached to its wheels and to the pole and body of the chariot. There seem to have been four horses to each chariot, and it will be obvious that if one of those horses was wounded by javelin or arrow, that chariot was held up. The outer horses acted chiefly as buffers for the inner wheel horses; they were hitched to the chariot by a single outside trace which could be easily cut away, but the loss of one of the wheel horses completely incapacitated the whole affair. Against broken footmen or a crowd of individualist fighters such vehicles might be formidable; but Darius began the battle by flinging them against the cavalry and light infantry. Few reached their objective, and those that did were readily disposed of. There was some manoeuvring for position. The well-drilled Macedonians moved obliquely across the Persian front, keeping good order; the Persians, following this movement to the flank, opened gaps in their array. Then suddenly the disciplined Macedonian cavalry charged at one of these torn places and smote the centre of the Persian host. The infantry followed close upon their charge. The centre and left of the Persians crumpled up. For a while the light cavalry on the Persian right gained ground against Alexander’s left, only to be cut to pieces by the cavalry from Thessaly, which by this time had become almost as good as its Macedonian model. The Persian forces ceased to resemble an army. They dissolved into a vast multitude of fugitives streaming under great dust clouds and without a single rally across the hot plain towards Arbela. Through the dust and the flying crowd rode the victors, slaying and slaying until darkness stayed the slaughter. Darius led the retreat.

Such was the battle of Arbela. It was fought on October the 1st, 331 B.C. We know its date so exactly, because it is recorded that, eleven days before it began, the soothsayers on both sides had been greatly exercised by an eclipse of the moon.

Darius fled to the north into the country of the Medes. Alexander marched on to Babylon. The ancient city of Hammurabi (who had reigned seventeen hundred years before) and of Nebuchadnezzar the Great and of Nabonidus was still, unlike Nineveh, a prosperous and important centre. Like the Egyptians, the Babylonians were not greatly concerned at a change of rule to Macedonian from Persian. The temple of Bel-Marduk was in ruins, a quarry for building material, but the tradition of the Chaldean priests still lingered, and Alexander promised to restore the building.

Thence he marched on to Susa, once the chief city of the vanished and forgotten Elamites, and now the Persian capital.

He went on to Persepolis, where, as the climax of a drunken carouse, he burnt down the great palace of the king of kings. This he afterwards declared was the revenge of Greece for the burning of Athens by Xerxes.

« 23.2 The Murder of King Philip |Contents | 23.4 The Wanderings of Alexander »

comments powered by Disqus