« 17.0 Gods and Stars, Priests and Kings |Contents | 17.2 Priests and the Stars »

17.1 The Priest Comes into History¶

When we direct our attention to these new accumulations of human beings that were beginning in Egypt and Mesopotamia, we find that one of the most conspicuous and constant objects in all these cities is a temple or a group of temples. In some cases there arises beside it in these regions a royal palace, but as often the temple towers over the palace. This presence of the temple is equally true of the ‘Phoenician cities and of the Greek and Roman as they arise. The palace of Cnossos, with its signs of comfort and pleasure- seeking, and the kindred cities of the Aegean peoples, include religious shrines, but in Crete there are also temples standing apart from the palatial city-households. All over the ancient civilized world we find them; wherever primitive civilization set its foot in Africa, Europe, or western Asia, a temple arose, and where the civilization is most ancient, in Egypt and in Sumer, there the temple is most in evidence. When Hanno reached what be thought was the most westerly point of Africa, he set up a temple to Hercules. The beginnings of civilization and the appearance of temples is simultaneous in history. The two things belong together. The beginning of cities is the temple stage of history.

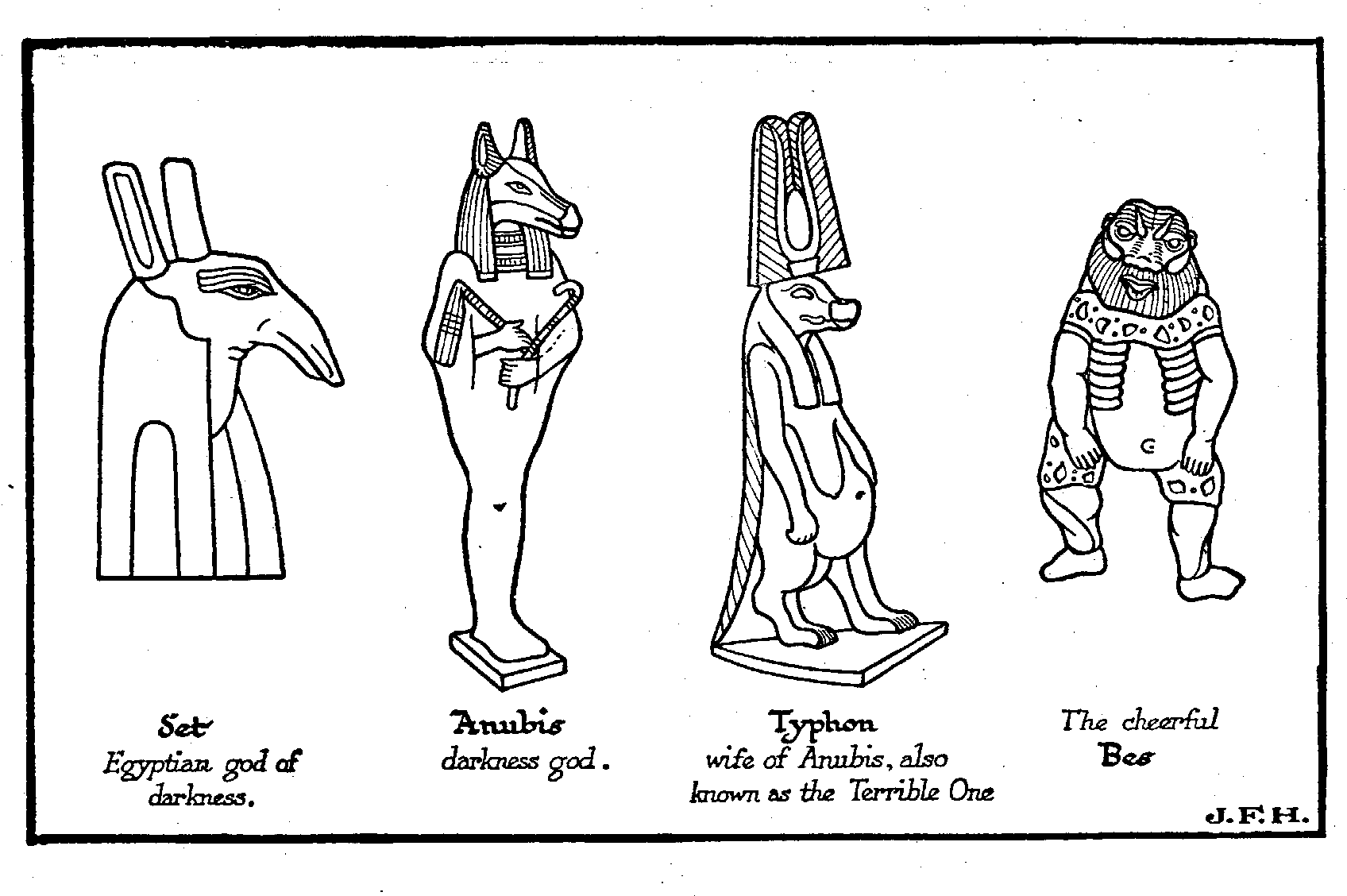

In all these temples there was a shrine; dominating the shrine there was commonly a great figure usually of some monstrous half-animal form, before which stood an altar for sacrifices. In the Greek and Roman temples however the image was generally that of a divinity in human form. This figure was either regarded as the god or as the image or symbol of the god, for whose worship the temple existed. And connected with the temple there were a number, and often a considerable number, of priests or priestesses, and temple servants, generally wearing a distinctive costume and forming an important part of the city population. They belong to no household; they made up a new kind of household of their own. They were a caste and a class apart, attracting intelligent recruits from the general population.

The primary duty of this priesthood was concerned with the worship of and the sacrifices to the god of the temple. And these things were done, not at any time, but at particular times and seasons. There had come into the life of man with his herding and agriculture a sense of a difference between the parts of the year and of a difference between day and day. Men were beginning to work — and to need days of rest. The temple, by its festivals, kept count. The temple in the ancient city was like the clock and calendar upon a writing-desk.

But it was a centre of other functions. It was in the early temples that the records and tallies of events were kept and that writing began. And there was knowledge there. The people went to the temple not only en masse for festivals, but individually for help. The early priests were also doctors and magicians. In the earliest temples we already find those little offerings for some private and particular end, which are still made in the chapels of Catholic churches today, ex votos, little models of hearts relieved and limbs restored, acknowledgment of prayers answered and accepted vows.

It is clear that here we have that comparatively unimportant element in the life of the early nomad, the medicine-man, the shrine-keeper, and the memorist, developed, with the development of the community and as a part of the development of the community from barbarism to civilized settlement, into something of very much greater importance. And it is equally evident that those primitive fears of (and hopes of help from) strange beings, the desire to propitiate unknown forces, the primitive desire for cleansing and the primitive craving for power and knowledge have all contributed to crystallize out this new social fact of the temple.

The temple was accumulated by complex necessities, it grew from many roots and needs, and the god or goddess that dominated the temple was the creation of many imaginations and made up of all sorts of impulses, ideas, and half ideas.

Here there was a god in which one sort of ideas predominated, and there another. It is necessary to lay some stress upon this confusion and variety of origin in gods, because there is a very abundant literature now in existence upon religious origins, in which a number of writers insist, some on this leading idea and some on that — we have noted several in our chapter on Early Thought — as though it were the only idea. Professor Max Miller in his time, for example, harped perpetually on the idea of sun stories and sun worship. He would have had us think that early man never had lusts or fears, cravings for power, nightmares or fantasies, but that he meditated perpetually on the beneficent source of light and life in the sky. Now dawn and sunset are very moving facts in the daily life, but they are only two among many. Early men, three or four hundred generations ago, had brains very like our own. The fancies of our childhood and youth are perhaps the best clue we have to the ground-stuff of early religion, and anyone who can recall those early mental experiences will understand very easily the vagueness, the monstrosity, and the incoherent variety of the first gods. There were sun gods, no doubt, early in the history of temples, but there were also hippopotamus gods and hawk gods; there were cow deities, there were monstrous male and female gods, there were gods of terror and gods of an adorable quaintness, there were gods who were nothing but lumps of meteoric stone that had fallen amazingly out of the sky, and gods who were mere natural stones that had chanced to have a queer and impressive shape. Some gods, like Marduk of Babylon and the Baal (= the Lord) of the Phoenicians, Canaanites, and the like, were quite probably at bottom just legendary wonder beings, such as little boys will invent for themselves today. The settled peoples, it is said, as soon as they thought of a god, invented a wife for him; most of the Egyptian and Babylonian gods were married. But the gods of the nomadic Semites had not this marrying disposition. Children were less eagerly sought by the inhabitants of the food grudging steppes.

Even more natural than to provide a wife for a god is to give him a house to live in to which offerings can be brought. Of this house the knowing man, the magician, would naturally become the custodian. A certain seclusion, a certain aloofness, would add greatly to the prestige of the god. The steps by which the early temple and the early priesthood developed so soon as an agricultural population settled and increased are all quite natural and understandable, up to the stage of the long temple with the image, shrine and altar at one end and the long nave in which the worshippers stood. And this temple, because it had records and secrets, because it was a centre of power, advice, and instruction, because it sought and attracted imaginative and clever people for its service, naturally became a kind of brain in the growing community. The attitude of the common people who tilled the fields and herded the beasts towards the temple would remain simple and credulous. There, rarely seen and so imaginatively enhanced, lived the god whose approval gave prosperity, whose anger meant misfortune; he could be propitiated by little presents and the help of his servants could be obtained. He was wonderful, and of such power and knowledge that it did not do to be disrespectful to him even in one’s thoughts. Within the priesthood, however, a certain amount of thinking went on at a rather higher level than that.

« 17.0 Gods and Stars, Priests and Kings |Contents | 17.2 Priests and the Stars »

comments powered by Disqus