« 15.1 The Earliest Ships and Sailors |Contents | 15.3 The First Voyages of Exploration »

15.2 The Aegean Cities before History¶

These early Cretans were of a race akin to the Iberians of Spain and Western Europe and the dark whites of Asia Minor and North Africa, and their language is unknown. This race lived not only in Crete, but in Cyprus, Greece, Asia Minor, Sicily, and South Italy. It was a civilized people for long ages before the fair Nordic Greeks spread southward through Macedonia. At Cnossos, in Crete, there have been found the most astonishing ruins and remains, and Cnossos, therefore, is apt to overshadow the rest of these settlements in people’s imaginations, but it is well to bear in mind that though Cnossos was no doubt a chief city of this Aegean civilization, these “Aegeans” had in the fullness of their time many cities and a wide range. Possibly, all that we know of them now are but the vestiges of the far more extensive heliolithic Neolithic civilization which is now submerged under the waters of the Mediterranean.

At Cnossos there are Neolithic remains as old or older than any of the pre- dynastic remains of Egypt. The Bronze Age began in Crete as soon as it did in Egypt, and there have been vases found by Flinders Petrie in Egypt and referred by him to the Ist Dynasty, which he declared to be importations from Crete. Stone vessels have been found in Crete of forms characteristic of the IVth (pyramid-building) Dynasty, and there can be no doubt that there was a vigorous trade between Crete and Egypt in the time of the XIIth Dynasty. This continued until about 1,000 B.C. It is clear that this island civilization arising upon the soil of Crete is at least as old as the Egyptian, and that it was already launched upon the sea as early as 4,000 B.C.

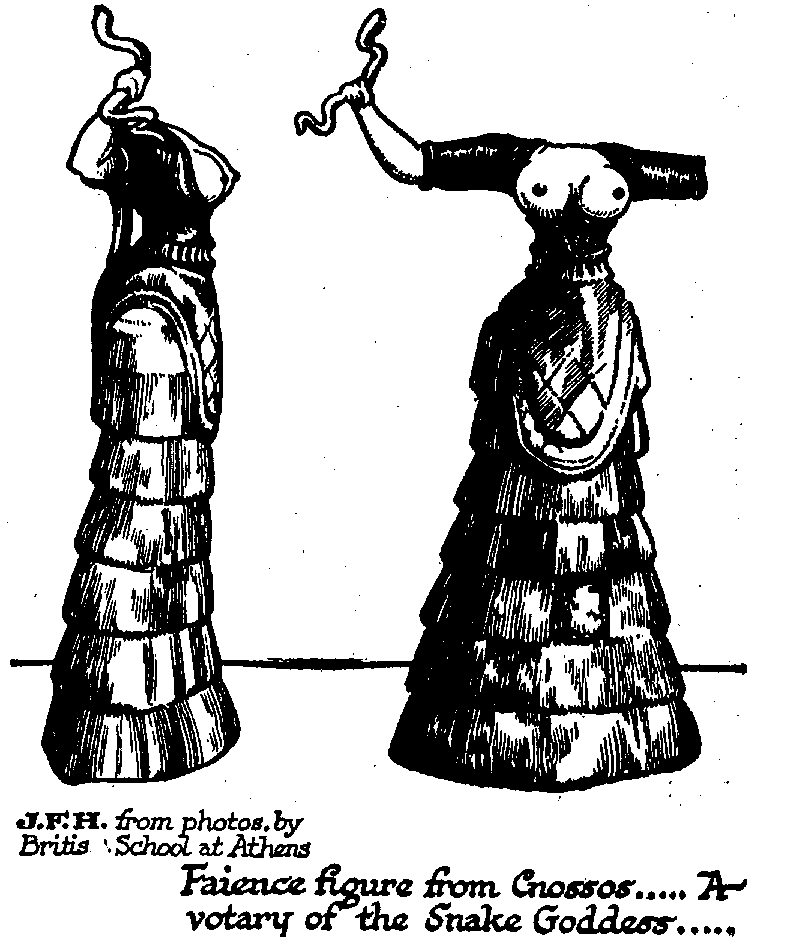

The great days of Crete were not so early as this. It was only about 2,500 B.C. that the island appears to have been unified under one ruler. Then began an age of peace and prosperity unexampled in the history of the ancient world. Secure from invasion, living in a delightful climate, trading with every civilized community in the world, the Cretans were free to develop all the arts and amenities of life. This Cnossos was not so much a town as the vast palace of the king and his people. It was not even fortified. The kings, it would seem, were called Minos always, as the kings of Egypt were all called Pharaoh; the king of Cnossos figures in the early legends of the Greeks as King Minos, who lived in the Labyrinth and kept there a horrible monster, half man, half bull, the Minotaur, to feed which he levied a tribute of youths and maidens from the Athenians. Those stories are a part of Greek literature, and have always been known, but it is only in the last few decades that the excavations at Cnossos have revealed how close these legends were to the reality. The Cretan labyrinth was a building as stately, complex, and luxurious as any in the ancient world. Among other details we find water- pipes, bathrooms, and the like conveniences, such as have hitherto been regarded as the latest refinements of modern life. The pottery, the textile manufactures, the sculpture and painting of these people, their gem and ivory work, their metal and inlaid work, is as admirable as any that mankind has produced. They were much given to festivals and shows, and, in particular, they were addicted to bull-fights and gymnastic entertainments. Their female costume became astonishingly ?modern? in style; their women wore corsets and flounced dresses. They had a system of writing which has not yet been deciphered.

It is the custom nowadays to make a sort of wonder of these achievements of the Cretans, as though they were a people of incredible artistic ability living in the dawn of civilization. But their great time was long past that dawn; as late as 2,000 B.C. It took them many centuries to reach their best in art and skill, and their art and luxury are by no means so great a wonder if we reflect that for 3,000 years they were immune from invasion, that for a thousand years they were at peace. Century after century their artisans could perfect their skill, and their men and women refine upon refinement. Wherever men of almost any race have been comparatively safe in this fashion for such a length of time, they have developed much artistic beauty. Given the opportunity, all races are artistic. Greek legend has it that it was in Crete that Daedalus attempted to make the first flying machine. Daedalus (= cunning artificer) was a sort of personified summary of mechanical skill. It is curious to speculate what germ of fact lies behind him and those waxen wings that, according to the legend, melted and plunged his son Icarus in the sea.

There came at last a change in the condition of the lives of these Cretans, for other peoples, the Greeks and the Phoenicians, were also coming out with powerful fleets upon the seas. We do not know what led to the disaster nor who inflicted it; but somewhen about 1,400 B.C. Cnossos was sacked and burnt, and though the Cretan life struggled on there rather lamely for another four centuries, there came at last a final blow about 1,000 B.C. (that is to say, in the days of the Assyrian ascendancy in the East). The palace at Cnossos was destroyed, and never rebuilt nor reinhabited. Possibly this was done by the ships of those new-comers into the Mediterranean, the barbaric Greeks, a group of Aryan-speaking tribes from the north, who may have wiped out Cnossos as they wiped out the city of Troy.

The legend of Theseus tells of such a raid. He entered the Labyrinth (which may have been the Cnossos Palace) by the aid of Ariadne, the daughter of Minos, and slew the Minotaur.

The Iliad makes it clear that destruction came upon Troy because the Trojans stole Greek women. Modern writers, with modern ideas in their heads, have tried to make out that the Greeks assailed Troy in order to secure a trade route or some such fine-spun commercial advantage. If so, the authors of the Iliad hid the motives of their characters very skillfully. It would be about as reasonable to say that the Homeric Greeks went to war with the Trojans in order to be well ahead with a station on the Berlin to Bagdad railway. The Homeric Greeks were a healthy barbaric Aryan people, with very poor ideas about trade and “trade routes”; they went to war with the Trojans because they were thoroughly annoyed about this stealing of women. It is fairly clear from the Minos legend and from the evidence of the Cnossos remains, that the Cretans kidnapped or stole youths and maidens to be slaves, bull-fighters, athletes, and perhaps sacrifices. They traded fairly with the Egyptians, but it may be they did not realize the gathering strength of the Greek barbarians; they “traded” violently with them, and so brought sword and flame upon themselves.

Another great sea people were the Phoenicians. They were great seamen because they were great traders. Their colony of Carthage (founded before 800 B.C. by Tyre) became at last greater than any of the older Phoenician cities, but already before 1,500 B.C. both Sidon and Tyre had settlements upon the African coast. Carthage was comparatively inaccessible to the Assyrian and Babylonian hosts, and, profiting greatly by the long siege of Tyre by Nebuchadnezzar II, became the greatest maritime power the world had hitherto seen. She claimed the Western Mediterranean as her own, and seized every ship she could catch west of Sardinia. Roman writers accuse her of great cruelties. She fought the Greeks for Sicily, and later (in the second century B.C.) she fought the Romans. Alexander the Great formed plans for her conquest; but he died, as we shall tell later, before he could carry them out.

« 15.1 The Earliest Ships and Sailors |Contents | 15.3 The First Voyages of Exploration »

comments powered by Disqus