« 33.1 Asia at the End of the Twelfth Century |Contents | 33.3 The Travels of Marco Polo »

33.2 The Rise and Victories of the Mongols¶

The career of conquest of Jengis Khan and his immediate successors astounded the world, and probably astounded no one more than these Mongol Khans themselves.

The Mongols were in the twelfth century a tribe subject to those Kin who had conquered North-east China. They were a horde of nomadic horsemen living in tents, and subsisting mainly upon mare’s milk products and meat. Their occupations were pasturage and hunting, varied by war. They drifted northward as the snows melted for summer pasture, and southward to winter pasture after the custom of the steppes. Their military education began with a successful insurrection against the Kin. The empire of Kin had the resources of half China behind it, and in the struggle the Mongols learnt very much of the military science of the Chinese. By the end of the twelfth century they were already a fighting tribe of exceptional quality.

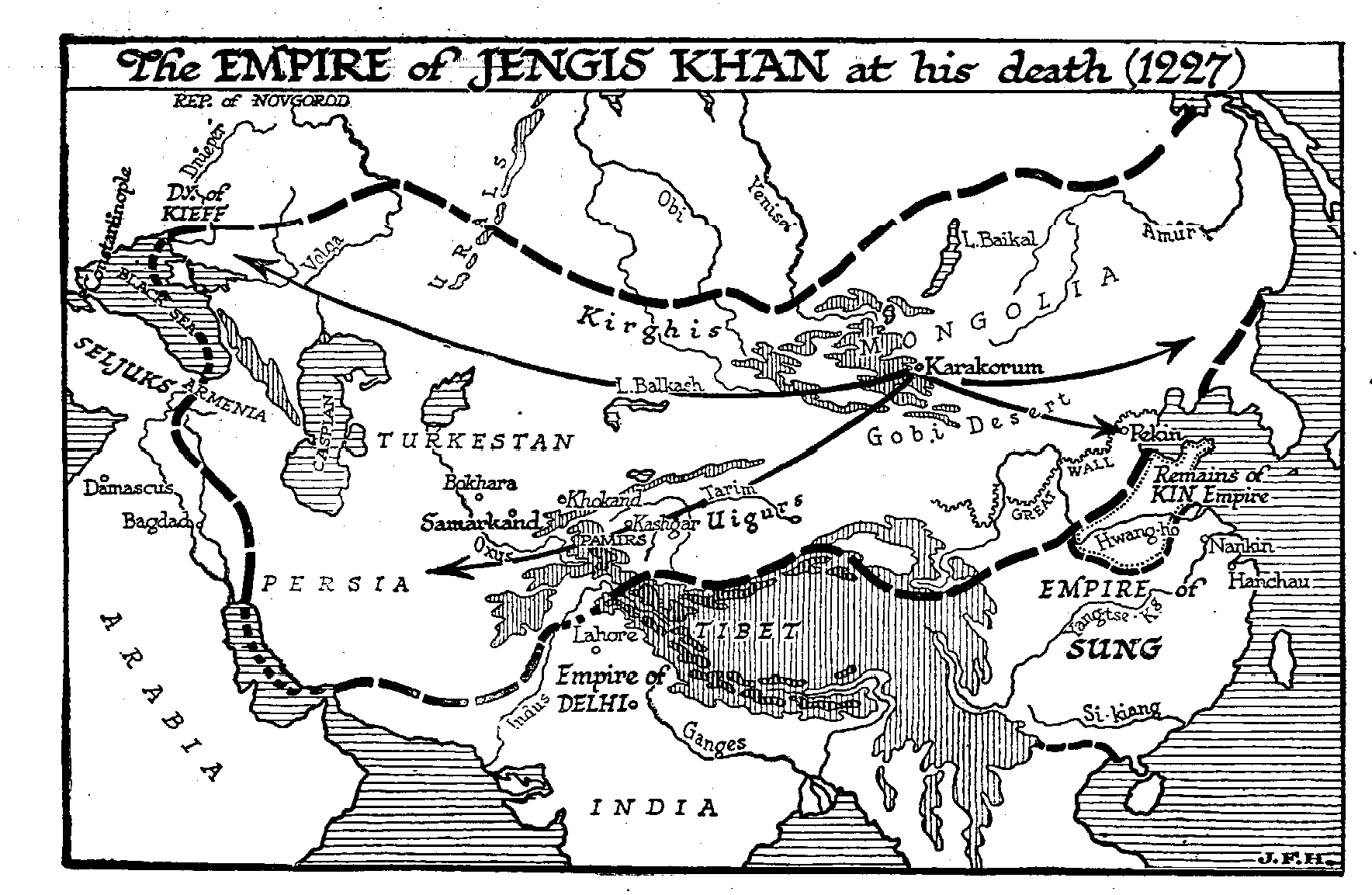

The opening years of the career of Jengis were spent in developing his military machine, in assimilating the Mongols and the associated tribes about them into one organized army. His first considerable extension of power was westward, when the Tartar Kirghis and the Uigurs (who were the Tartar people of the Tarim basin) were not so much conquered as induced to join his organization. He then attacked the Kin Empire and took Pekin (1214). The Khitan people, who had been so recently subdued by the Kin, threw in their fortunes with his, and were of very great help to him. The settled Chinese population went on sowing and reaping and trading during this change of masters without lending its weight to either side.

We have already mentioned the very recent Kharismian Empire of Turkestan, Persia, and North India. This empire extended eastward to Kashgar, and it must have seemed one of the most progressive and hopeful empires of the time. Jengis Khan, while still engaged in this war with the Kin Empire, sent envoys to Kharismia. They were put to death, an almost incredible stupidity. The Kharismian government, to use the political jargon of today, had decided not to «recognize» Jengis Khan, and took this spirited course with him. There upon (1218) the great host of horsemen that Jengis Khan had consolidated and disciplined swept over the Pamirs and down into Turkestan. It was well armed, and probably it had some guns and gunpowder for siege work for the Chinese were certainly using gunpowder at this time, and the Mongols learnt its use from them. Kashgar, Khokand, Bokhara fell and then Samarkand, the capital of the Kharismian empire. There after nothing held the Mongols in the Kharismian territories. They swept westward to the Caspian, and southward as far as Lahore. To the north of the Caspian a Mongol army encountered a Russian force from Kieff. There was a series of battles, in which the Russian armies were finally defeated and the Grand Duke of Kieff taken prisoner.

So it was the Mongols appeared on the northern shores of the Black Sea. A panic swept Constantinople, which set itself to reconstruct its fortifications. Meanwhile other armies were engaged in the conquest of the empire of the Asia in China. This was annexed, and only the southern part of the Kin Empire remained unsubdued. In 1227 Jengis Khan died in the midst of a career of triumph. His empire reached already from the Pacific to the Dnieper. And it was an empire still vigorously expanding.

Like all the empires founded by nomads, it was, to begin with, purely a military and administrative empire, a framework rather than a rule. It centered on the personality of the monarch, and its relations with the mass of the populations over which it ruled was simply one of taxation for the maintenance of the horde. But Jengis Khan had called to his aid a very able and experienced administrator of the Kin Empire, who was learned in all the traditions an science of the Chinese.

This statesman, Yeliu Chutsai, was able to carry on the affairs of the Mongols long after the death of Jengis Khan, and there can be little doubt that he is one of the great political heroes of history. He tempered the barbaric ferocity of his masters, and saved innumerable cities and works of art from destruction. He collected archives and inscriptions, and when he was accused of corruption, his sole wealth was found to consist of documents and a few musical instruments. To him perhaps quite as much as to Jengis is the efficiency of the Mongol military machine to be ascribed. Under Jengis, we may note further, we find the completest religious toleration established across the entire breadth of Asia.

At the death of Jengis the capital of the new empire was still in the great an assembly of Mongol leaders elected Ogdai Khan, the son of Jengis, as his successor. The war against the vestiges of the Kin Empire was prosecuted until Kin was altogether subdued (1234). The Chinese empire to the south under the Sung dynasty helped the Mongols in this task, so destroying their own bulwark against the universal conquerors. The Mongol hosts then swept right across Asia to Russia (1235) , an amazing march. Kieff was destroyed in 1240, and nearly all Russia became tributary to the Mongols. Poland was ravaged, and a mixed army of Poles and Germans was annihilated at the battle of Liegnitz in Lower Silesia in 1241. The Emperor Frederick II does not seem to have made any great efforts to stay the advancing tide.

«It is only recently», says Bury in his notes to Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire «, that European history has begun to understand that the successes of the Mongol army which overran Poland and occupied Hungary in the spring of A.D. 1241 were won by consummate strategy and were not due to a mere overwhelming superiority of numbers. But this fact has not yet become a matter of common knowledge; the vulgar opinion which represents the Tartars as a wild horde carrying all before them solely by their multitude, and galloping through Eastern Europe without a strategic plan, rushing at all obstacles and overcoming them by mere weight, still prevails …

«It was wonderful how punctually and effectually the arrangements of the commander were carried out in operations extending from the Lower Vistula to Transylvania. Such a campaign was quite beyond the power of any European army of the time, and it was beyond the vision of any European commander. There was no general in Europe, from Frederick II downward, who was not a tyro in strategy compared to Subutai. It should also be noticed that the Mongols embarked upon the enterprise with full knowledge of the political situation of Hungary and the condition of Poland they had taken care to inform themselves by a well organized system of spies; on the other hand, the Hungarians and Christian powers, like childish barbarians, knew hardly anything about their enemies».

But though the Mongols were victorious at Liegnitz, they did not continue their drive westward. They were getting into woodlands and hilly country, which did not suit their tactics; and so they turned southward and prepared to settle in Hungary, massacring or assimilating the kindred Magyar, even as these had previously massacred and assimilated the mixed Scythians and Avars and Huns before them. From the Hungarian plain they would probably have made raids west and south as the Hungarians had done in the ninth century, the Avars in the seventh and eighth, and the Huns in the fifth. But in Asia the Mongols were fighting a stiff war of conquest against the Sung, and, they were also raiding Persia and Asia Minor; Ogdai died suddenly, and in 1242 there was trouble about the succession, and recalled by this, the undefeated hosts of Mongols began to pour back across Hungary and Rumania towards the east.

To the great relief of Europe the dynastic troubles at Karakorum lasted for some years, and this vast new empire showed signs of splitting up. Mangu Khan became the Great Khan in 1251, and he nominated his brother Kublai Khan as Governor General of China. Slowly but surely the entire Sung empire was subjugated, and as it was subjugated the eastern Mongols became more and more Chinese in their culture and methods. Tibet was invaded and devastated by Mangu, and Persia and Syria invaded in good earnest. Another brother of Maugu, Hulagu, was in command of this latter war; He turned his arms against the caliphate and captured Bagdad, in which city he perpetrated a massacre of the entire population. Bagdad was still the religious capital of Islam, and the Mongols had become bitterly hostile to the Moslems. This hostility exacerbated the natural discord of nomad and townsman. In 1259 Mangu died, and in 1260—for it took the best part of a year for the Mongol leaders to gather from the extremities of this vast empire, from Hungary and Syria and Seind and China—Kublai was elected Great Khan. He was already deeply interested in Chinese affairs; he made his capital Pekin instead of Karakorum, and Persia, Syria, and Asia Minor became virtually independent under his brother Hulagu, while the hordes of Mongols in Russia and Asia next to Russia, and various smaller Mongol groups in Turkestan became also practically separate. Kublai died in 1294, and with his death even the titular supremacy of the Great Khan disappeared.

At the death of Kublai there was a main Mongol empire, with Pekin as its capital, including all China and Mongolia; there was a second great Mongol empire, that of Kipchak in Russia; there was a third in Persia, that founded by Hulagu, the Ilkhan empire, to which the Seljuk Turks in Asia Minor were tributary; there was a Siberian state, between Kipchak and Mongolia; and another separate state «Great Turkey» in Turkestan. It is particularly remarkable that India beyond the Punjab was never invaded by the Mongols during this period, and that an army under the Sultan of Egypt completely defeated Ketboga, Hulagu’s general, in Palestine (1260), and stopped them from entering Africa. By 1260 the impulse of Mongol conquest had already passed its zenith. Thereafter the Mongol story is one of division and decay.

The Mongol dynasty that Kublai Khan had founded in China, the Yuan dynasty lasted from 1280 until 1368. Later on a recrudescence of Mongolian energy in Western Asia was destined, to create a still more enduring monarchy in India.

« 33.1 Asia at the End of the Twelfth Century |Contents | 33.3 The Travels of Marco Polo »

comments powered by Disqus