« 33.3 The Travels of Marco Polo |Contents | 33.5 Why the Mongols were not Christianized »

33.4 The Ottoman Turks and Constantinople¶

These travels of Marco Polo were only the beginning of a very considerable intercourse. That intercourse was to bring many revolutionary ideas and many revolutionary things to Europe, including a greatly extended use of paper and printing from blocks, the almost equally revolutionary use of gunpowder in warfare, and the mariner’s compass which was to release the European shipping from navigation by coasting. The popular imagination has always been disposed to ascribe every such striking result to Marco Polo. He has become the type and symbol for all such interchanges. As a matter of fact, there is no evidence that he had any share in these three importations. There were many mute Marco Polos who never met their Rusticianos, and history has not preserved their names. Before we go on, however, to, describe the great widening of the mental horizons of Europe that was now beginning, and to, which this book of travels was to contribute very materially, it will be convenient first to note a curious side consequence of the great Mongol conquests, the appearance of the Ottoman Turks upon the Dardanelles, and next to state in general terms the breaking up and development of the several parts of the empire of Jengis Khan.

The Ottoman Turks were a little band of fugitives who fled southwesterly before the first invasion of Western Turkestan by Jengis. They made their long way from Central Asia, over deserts and mountains and through alien populations, seeking some new lands in which they might settle. «A small band of alien herdsmen», says Sir Mark Sykes, «wandering unchecked through crusades and counter-crusades, principalities, empires, and states. Where they camped, how they moved and preserved their flocks and herds, where they found pasture, how they made their peace with the various chiefs through whose territories they passed, are questions which one may well ask in wonder».

They found a resting-place at last and kindred and congenial neighbours on the tablelands of Asia Minor among the Seljuk Turks. Most of this country, the modern Anatolia, was now largely Turkish in speech and Moslem in religion, except that there was a considerable proportion of Greeks, Jews, and Armenians in the town populations. No doubt the various strains of Hittite, Phrygian, Trojan, Lydian, Ionian Greek, Cimmerian, Galatian, and Italian (from the Pergamus times) still flowed in the blood of the people, but they had long since forgotten these ancestral elements. They were indeed much the same blend of ancient Mediterranean dark whites, Nordic Aryans, Semites and Mongolians as were the inhabitants of the Balkan peninsula, but they believed themselves to be a pure Turanian race, and altogether superior to the Christians on the other side of the Bosphorus.

Gradually the Ottoman Turks became important, and at last dominant among the small principalities into which the Seljuk Empire, the empire of «Roum», had fallen. Their relations with the dwindling empire of Constantinople remained for some centuries tolerantly hostile. They made no attack upon the Bosphorus, but they got a footing in Europe at the Dardanelles, and, using this route, the route of Xerxes and not the route of Darius, they pushed their way steadily into Macedonia, Epirus, Illyria, Yugo-Slavia, and Bulgaria. In the Serbs (Yugoslavs) and Bulgarians the Turks found people very like themselves in culture and, though neither side recognized it, probably very similar in racial admixture, with a little less of the dark Mediterranean and Mongolian strains than the Turks and a trifle more of the Nordic element. But these Balkan peoples were Christians, and bitterly divided among themselves. The Turks on the other hand spoke one language; they had a greater sense of unity, they had the, Moslem habits of temperance and frugality, and they were on the whole better soldiers. They converted what they could of the conquered people to Islam; the Christians they disarmed, and conferred upon them the monopoly of tax paying. Gradually the Ottoman princes consolidated an, empire that reached from Taurus Mountains in the east to Hungary and Roumania in the west. Adrianople became their chief city. They surrounded the shrunken empire of Constantinople on every side.

The Ottomans organized a standing military force, the Janissaries, rather on the lines of the Mamelukes of dominated Egypt. These troops were formed of levies of Christian youths to the extent of one thousand per annum, who were affiliated to the Bektashi order of dervishes, and though at first not obliged to embrace Islam, were one and all strongly imbued with the mystic and fraternal ideas of the confraternity to which they were attached. Highly, paid, well disciplined, a close and jealous secret society, the Janissaries provided the newly formed Ottoman state with a patriotic force of trained infantry soldiers, which, in an age of light cavalry and hired companies of mercenaries, was an invaluable asset …

«The relations between the Ottoman Sultans and the Emperors has been singular in the annals of Moslem and Christian states. The Turks had been involved in the family and dynastic quarrels of the Imperial City, were bound by ties of blood to the ruling families, frequently supplied troops for the defense of Constantinople, and on occasion hired parts of its garrison to assist them in their various campaigns; the sons of the Emperors and Byzantine statesmen even accompanied the Turkish forces in the field, yet the Ottomans never ceased to annex Imperial territories and cities both in Asia and Thrace. This curious intercourse between the House of Osman and the Imperial government had a profound effect on both institutions; the Greeks grew more and more debased and demoralized by the shifts and tricks that their military weakness obliged them to adopt towards their neighbours, the Turks were corrupted by the alien atmosphere of intrigue and treachery which crept into their domestic life. Fratricide and parricide, the two crimes which most frequently stained the annals of the Imperial Palace, eventually formed a part of the policy of the Ottoman dynasty. One of the sons of Murad I embarked on an intrigue with Andronicus, the son of the Greek Emperor, to murder their respective fathers . . .

«The Byzantine found it more easy to negotiate with the Ottoman Pasha than with the Pope. For years the Turks and Byzantines had intermarried, and hunted in couples in strange bypaths of diplomacy. The Ottoman had played the Bulgar and the Serb of Europe against the Emperor, just as the Emperor had played the Asiatic Amir against the Sultan; the Greek and Turkish Royal Princes had mutually agreed to hold each other’s rivals as prisoners and hostages; in fact, Turk and Byzantine policy had so intertwined that it is difficult to say whether the Turks regarded the Greeks as their allies, enemies, or subjects, or whether the Greeks looked upon the Turks as their tyrants, destroyers, or protectors. . . ».[1]

It was in 1453, under the Ottoman Sultan, Muhammad II, that Constantinople last fell to, the Moslems. He attacked it from the European side, and with a great power of artillery. The Greek Emperor was killed, and there was much looting and massacre. The great church of St. Sophia, which Justinian the Great had built (532) was plundered of its treasures and turned at once into a mosque. This event sent, a wave of excitement throughout Europe, and an attempt was made to organize a crusade, but the days of the crusades were past.

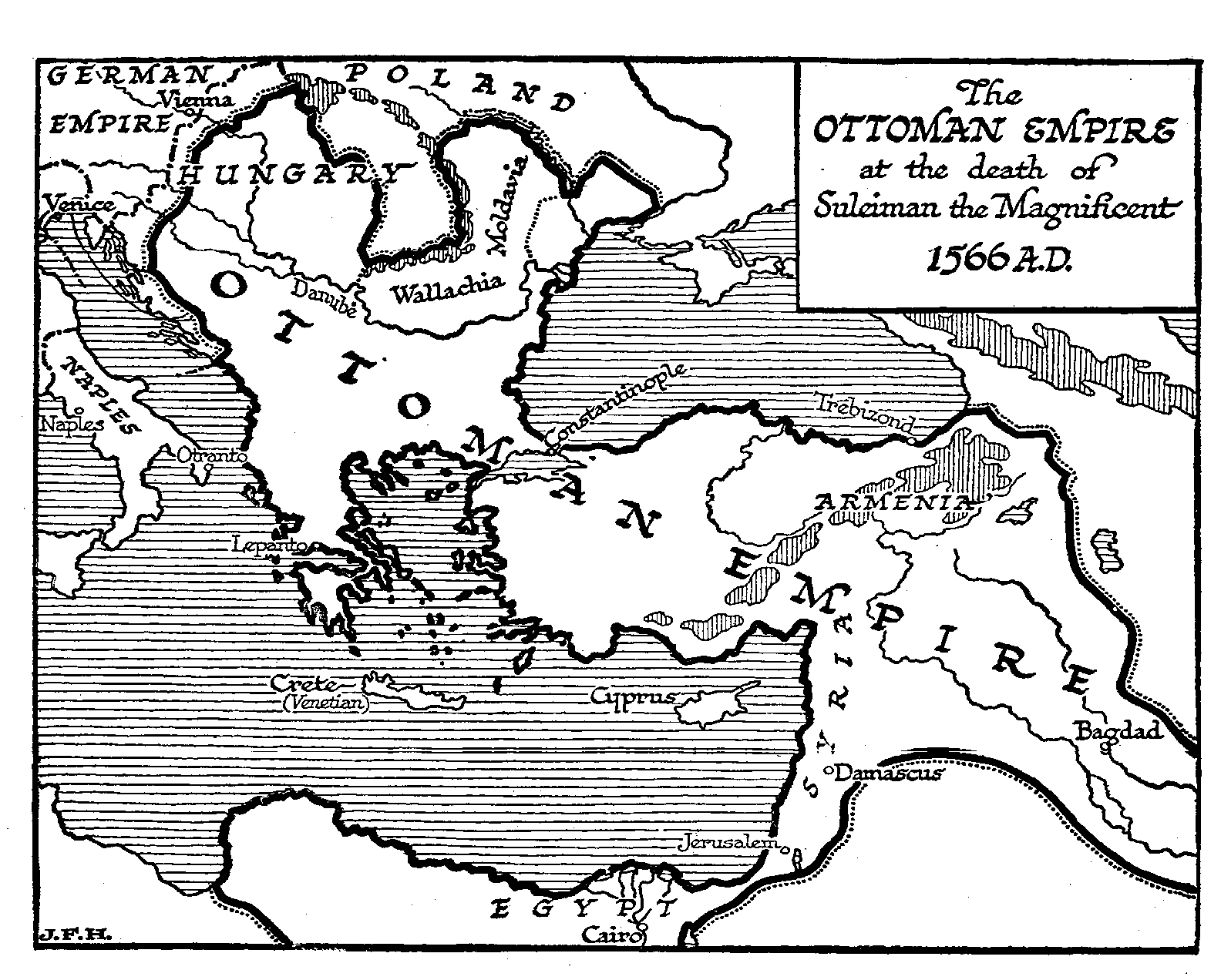

Figure 686: Map — Ottoman Empire, 1566

Says Sir Mark Sykes: «To, the Turks the capture of Constantinople was a crowning mercy and yet a fatal blow. Constantinople had been the tutor and polisher of the Turks. So long as the Ottomans could draw science, learning, philosophy, art, and tolerance from a living fountain of civilization in the heart of their dominions, so long had the Ottomans not only brute force, but intellectual power. So long as the Ottoman Empire had in Constantinople a free port, a market, a centre of world finance, a pool of gold, an exchange, so long did the Ottomans never lack for money and financial support. Muhammad was a great statesman, the moment he entered Constantinople be endeavoured to stay the damage his ambition had done; he supported the patriarch, he conciliated the Greeks, he did all he could to continue Constantinople the city of the Emperors … but the fatal step had been taken, Constantinople as the city of the Sultans was Constantinople no more; the markets died away, the culture and civilization fled, the complex finance faded from sight; and the Turks had lost their governors and their support. On the other hand, the corruptions of Byzantium remained, the bureaucracy, the eunuchs, the palace guards, the spies, and the bribers, go-betweens—all these the Ottomans took over, and all these survived in luxuriant life. The Turks, in taking Stambul, let slip a treasure and gained a pestilence . . ».

Muhammad’s ambition was not sated by the capture of Constantinople. He set his eyes also upon Rome. He captured and looted the Italian town of Otranto, and it is probable that a very vigorous and perhaps successful attempt to conquer Italy for the peninsula was divided against itself was averted only by his death (1481). His sons engaged in fratricidal strife. Under Bayezid II (1481-1512), his successor, war was carried into Poland, and most of Greece was conquered. Selim (1512-1520), the son of Bayezid, extended the Ottoman power over Armenia and conquered Egypt. In Egypt, the last Abbasid Caliph was living under the protection of the Mameluke Sultan—for the Fatimite caliphate was a thing of the past. Selim bought the title of Caliph from this last degenerate Abbasid, and acquired the sacred banner and other relies of the Prophet. So the Ottoman Sultan became also Caliph of all Islam. Selim was followed by Suleiman the Magnificent (1520-1566), who conquered Bagdad in the east and the greater part of Hungary in the west, and very nearly captured Vienna.

His fleets also took Algiers, and inflicted a number of reverses upon the Venetians. In most of his warfare with the empire he was in alliance with the French. Under him the Ottoman power reached its zenith.

| [1] | Sir Mark Sykes, The Caliphs’ Last Heritage. |

« 33.3 The Travels of Marco Polo |Contents | 33.5 Why the Mongols were not Christianized »

comments powered by Disqus