« 39.12 Summary of the First Covenant of the League of Nations |Contents | 39.14 A Forecast of the Next War »

39.13 A General Outline of the Treaties of 1919 and 1920¶

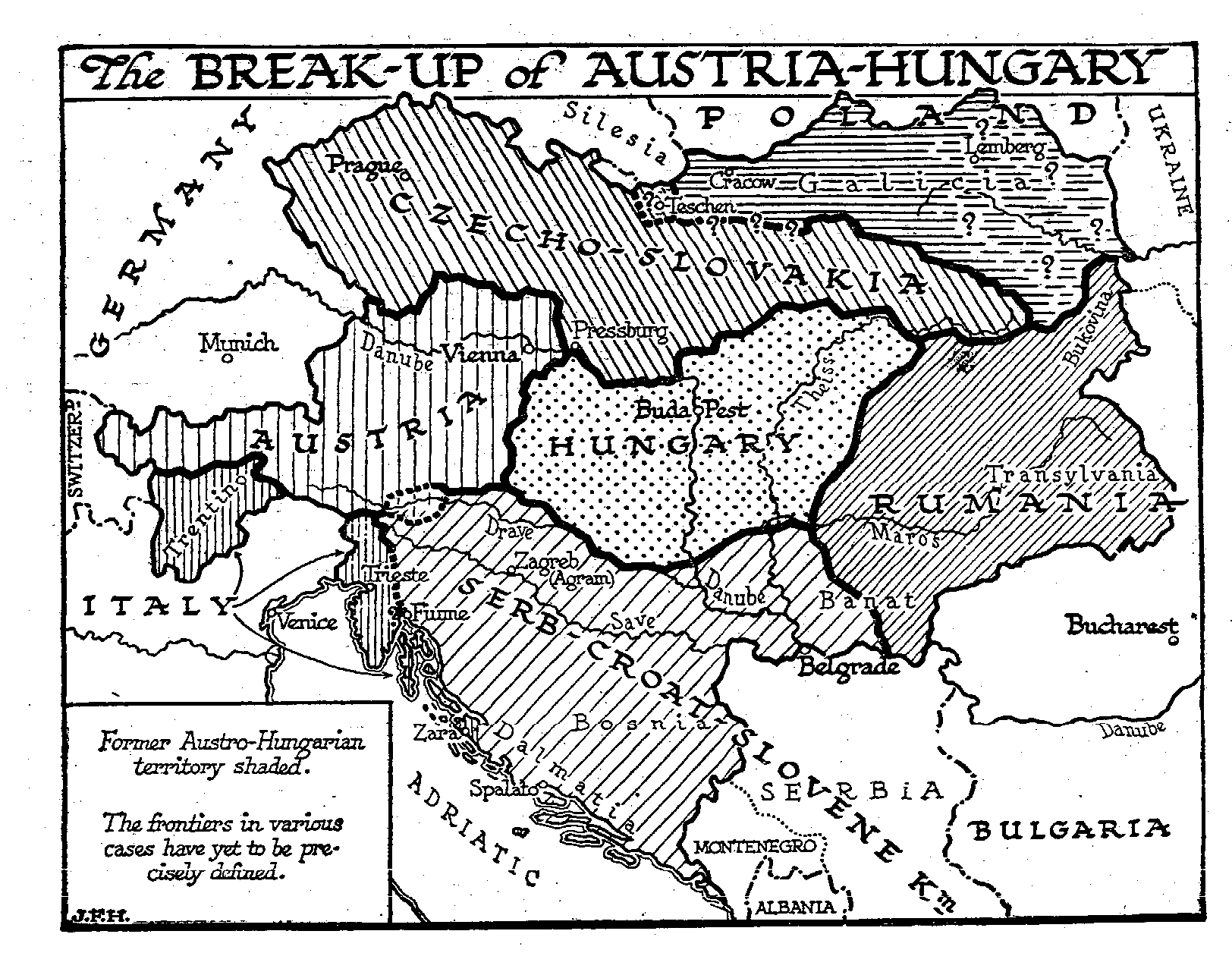

The main terms of the Treaties of 1919-20 with which the Conference of Paris concluded its labors can be stated much more vividly by a few maps than by a written abstract. We need scarcely point out how much those treaties, left unsettled, but we may perhaps enumerate some of the more salient breaches of the Twelve that survived out of the Fourteen Points at the opening of the Conference.

One initial cause of nearly all those breaches lay, we believe, in the complete unpreparedness and unwillingness of that preexisting league of nations, subjected states and exploited areas, the British Empire, to submit to any dissection and adaptation of its system or to any control of its naval and aerial armament. A kindred contributory cause was the equal unpreparedness of the American mind for any interference with the ascendancy of the United States in the New World (compare Secretary Olney’s declaration in this chapter, sec 6). Neither of those Great Powers, who were necessarily dominant and leading powers at Paris, had properly thought out the implications of a League of Nations in relation to these older arrangements, and so their support of that project had to most European observers a curiously hypocritical air; it was as if they wished to retain and ensure their own vast predominance and security while at the same time restraining any other power from such expansions, annexations, and alliances as might create a rival and competitive imperialism. Their failure to set an example of international confidence destroyed all possibility of international confidence in the other nations represented at Paris.

Even more unfortunate was the refusal of the Americans to assent to the Japanese demand for recognition of racial equality.

Moreover, the foreign offices of the British, the French, and the Italians were haunted by traditional schemes of aggression entirely incompatible with the new ideas. A League of Nations that is to be of any appreciable value to mankind must supersede imperialisms; it is either a super-imperialism, a liberal world-empire of united states, participant or in tutelage, or it is nothing; but few of the people at the Paris Conference had the mental vigor even to assert this obvious consequence of the League proposal. They wanted to be at the same time bound and free, to ensure peace forever, but to keep their weapons in their hands. Accordingly the old annexation projects of the Great Power period were hastily and thinly camouflaged as proposed acts of this poor little birth of April 28th. The newly born and barely animate League was represented to be distributing, with all the reckless munificence of a captive pope, «mandates» to the old imperialisms that, had it been the young Hercules we desired, it would certainly have strangled in its cradle.

Britain was to have extensive «mandates» in Mesopotamia and East Africa; France was to have the same in Syria; Italy was to have all her holdings to the west and southeast of Egypt consolidated as mandatory territory. Clearly, if the weak thing that was being nursed by its Secretary in its cradle at Geneva into some semblance of life, did presently succumb to the, infantile weakness of all institutions born without passion, all these «mandates» would become frank annexations. Moreover, all the Powers fought tooth and nail at the Conference for «strategic» frontiers the ugliest symptom of all. Why should a state want a strategic frontier unless it contemplates war? If on that plea Italy insisted upon a subject population of Germans in the southern Tyrol and a subject population of Yugo-Slavs in Dalmatia, and if little Greece began landing troops in Asia Minor, neither France nor Britain was in a position to rebuke these outbreaks of pre- millennial method.

We will not enter here into any detailed account of how President Wilson gave way to the Japanese and consented to their replacing the Germans at Kiau Chau, which is Chinese property, how the almost purely German city of Danzig was practically, if not legally, annexed, to Poland, and how the Powers disputed over the claim of the Italian imperialists, a claim strengthened by these instances, to seize the Yugo-Slav port of Fiume and deprive the Yugo-Slavs of a good Adriatic outlet. Nor will we do more than note the complex arrangements and justifications that put the French in possession of the Saar valley, which is German territory, or the entirely iniquitous breach of the right of «self-determination» which practically forbade German Austria to unite as it is natural and proper that she should unite with the rest of Germany. These burning questions of 1919-20, which occupied the newspapers and the minds of statesmen and politicians, and filled all our wastepaper baskets with propaganda literature, may seem presently very incidental things in the larger movement of these times. All these disputes, like the suspicions and tetchy injustices of a weary and irritated man, may lose their importance as the tone of the world improves, and the still inadequately apprehended lessons of the Great War and the Petty Peace that followed it begin to be digested by the general intelligence of mankind.

It is worthwhile for the reader to compare the treaty maps we give with what we have called the natural political map of Europe. The new arrangements do approach this latter more closely than any previous system of boundaries. It may be a necessary preliminary to any satisfactory league of peoples that each people should first be in something like complete possession of its own household.

« 39.12 Summary of the First Covenant of the League of Nations |Contents | 39.14 A Forecast of the Next War »

comments powered by Disqus